“It looks great in my hand but it sucks during warfare,” claimed Jean Dark. “Kind of a double-edged sword.”

Photo by Sharon Roth

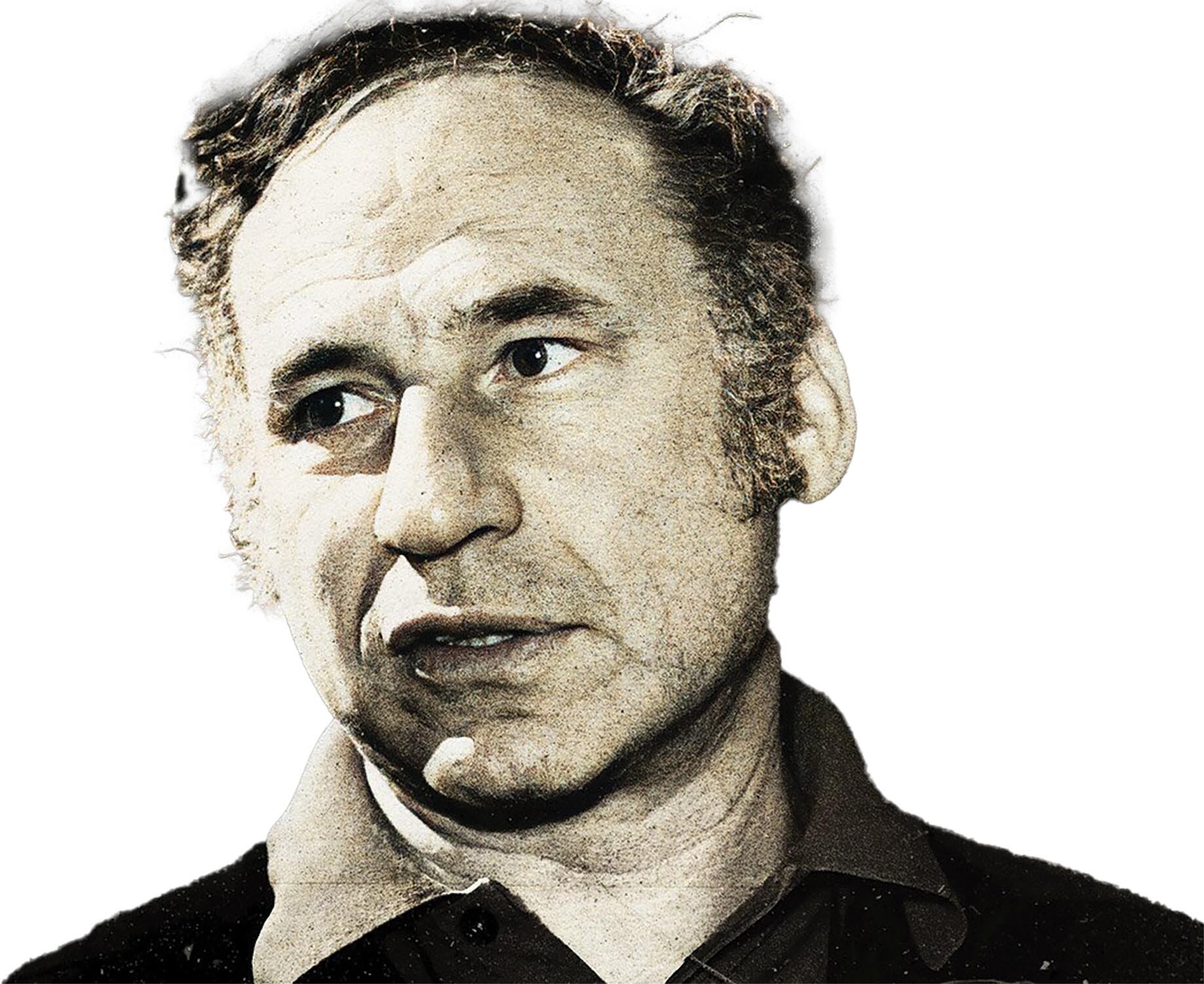

The workshop of Trevor McLintosh is cold and pristine, with bright lights hanging overhead and a team of apprentices each wearing the same casual work robes, so as to distinguish themselves from the hoard of customers that enter their workshop each day. Their apprentice seal, a biblical motif, is identical to the one emblazoned on the hilt of each of McLintosh’s celebrated swords. As one fan puts it, “With a single glance into the heat of a stoked kiln, anyone can see the dedication and craftsmanship that goes into each sword here,” before adding an aside, “I’m so glad I get to come here every year, almost on the dot, right as my glorious sword slays my thousandth foe and collapses into itself, accidentally stabbing me in the process.”

“These guys have dominated the market ever since Trevor McLintosh figured out how to perfectly calibrate swords to their wielders, inventing the iSword in the process. But somewhere along the way, the iSword I’d bought would end up falling apart, and I’d have to buy a new one,” claimed Jean Dark, an up-and-coming soldier on her first siege. “I’m up to the iSword X dual-wielding, and I paid an extra gold ingot for the lapis lazuli sheaths, which I’m so happy with. But still.”

That is one of the many complaints soldiers and infantrymen alike have had with weapons made in this shop. “I feel like right as McLintosh leaves his workshop and a herald announces his newest design, my own sword starts performing so poorly that I’m forced to buy a new one,” said Owain Argent, local munition man. “This man must have been given the gift of prophecy, to know just when I am going to need a new weapon! Truly, Trevor McLintosh has been given many blessings, apart from inherited wealth, to be so perceptive of my needs as a customer. He really fills the niche made by people who have both filled pockets and a burning desire not to get killed by enemy combatants.”

Recently, McLintosh has started expanding his clientele, adding new spins on a plethora of bows to the joy of archers everywhere. “I just bought a whole quiver of arrowheads from here, and the craftsmanship is unlike anything I’ve ever seen before,” exclaimed Dark, before hurriedly buying the official McLintosh whetstone to sharpen her new arrows, as all other whetstones from any other blacksmith “would be incompatible.”

“Sure, sometimes swords break,” acknowledged McLintosh, “however, I’m working on a new project that would keep all my customers’ swords up-to-date on everything they would ever need.” These fixes, colloquially called “updates,” have sword owners come into the blacksmith for improvements to their already purchased swords for no cost. It is, claimed McLintosh, a universally beloved practice, that allows the sword wielder to feel like a part of a “wonderful, constantly-expanding conversation” in smithing.

“I hate it,” Argent said. “Everyone I know hates it. My handle’s no longer got the same grooves and wears I’ve tirelessly worked my hands into while practicing with it, and I know one of my friend’s companions died because they forgot to account for the new chain length of their updated morning star. The only reason any of us come back to get these updates done is because a pigeon comes to our doorstep every day to give us the message that up-to-date installments are available to us now. It’s so annoying.”

The last straw for many happened recently, when McLintosh got rid of sword hilts entirely, and created an apparatus to be inserted through the arm to allow for “better ease of motion.”

Former Editor-in-Chief. Like an ouroboros, her jokes consume themselves until no one knows whether they were ever funny. But they are.