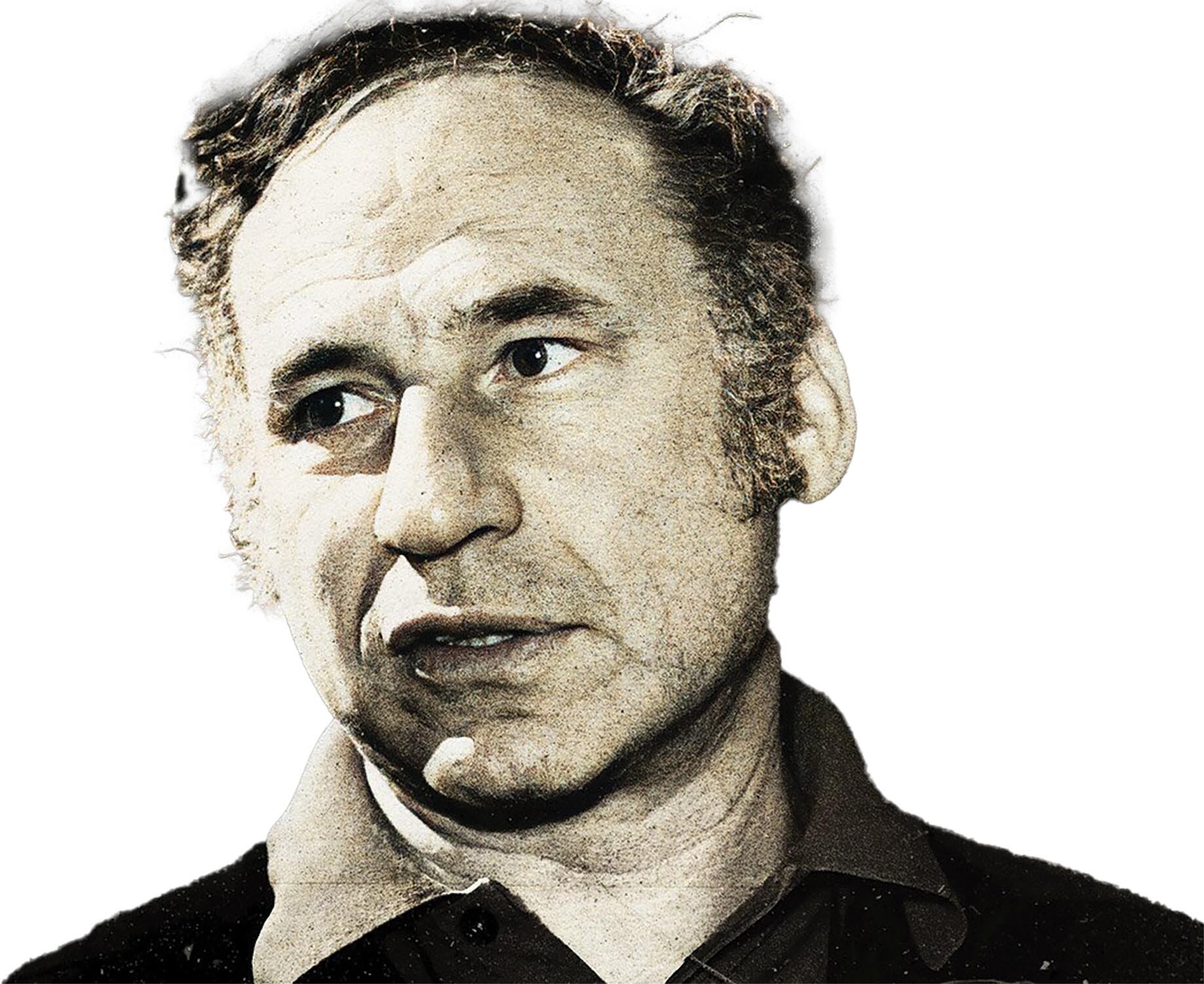

I WENT TO REGGIO CALABRIA to find the missing piece. After almost 20 years since my last visit, I returned to solve a mystery.

The mystery in question was the unusual passings of several Italian matriarchs. It caught my interest almost by accident. I was glancing in some of my locked drawers at random photocopied sheets of Southern Italian Census updates for no real reason, and noted the uptick in deaths of women over the last 50 years. Strange, I thought to myself, with no intention of looking further. But three days, three months, and three years after my initial discovery, I was running on fumes, unearthing more and more with each question I forced myself to ask, arms wide in pleading desperation.

I am not writing this to make anyone feel guilty. Believe me, if I could save us from the realization, I would. But this is not what they deserved. Their continued suffering is not worth my silence.

And that’s what led me to this place. One last stop before I tell the world: Reggio Calabria. Gorgeous, seaside, quintessentially Italian in a way hard to describe. And the center of it all.

At the very tip of the boot that many presume to see whenever looking at Italy on a map, Reggio Calabria is easy to miss. Looking upon it, standing with my back to the salty spray of the sea, I could see everything from afar. I imagined my life differently: a little bambina skipping upon these cobbled stones, my hand waving at the locals who I knew and who knew me, eyes barely noticing sights so full of the bounties of history and culture, being to me mere commonplace glimmers, tarnished by everyday routine. Perhaps there might have been a childhood fear: looking at my home on a map and realizing its teetering position so close to the edge. Maybe I would have woken myself up from nightmares, imagining myself beholden to the capricious leg of the boot, who could at any instance scrape me off — and plunge me into the sea.

But this was not my life. These are not the memories of a transplanted child, now adult, or even the secondhand retellings of a slurring, red-faced aunt. I am, to my great shame, Dutch-Armenian — not a single drop of Italian blood pulses through my veins. I went once, as a child, while on a Norwegian cruise ship, but all that can be proven of that quick jaunt is a blurry photo of my grasping, chubby toddler hands intent on pushing up the Tower of Pisa, and the certainty I feel right now. I can sense something here. Something undeniable.

There is an energy to this place. Looking deeper into the speckled, Italian waters off the coast, my arms prickled with the sharp pins of goosebumps, I wondered: perhaps there is a fear. There is something dark here, in Reggio Calabria. Something twisted and angry, biding its time in the seedy underbelly of this quaint town. No one admits to it. Of course, no one could. But I see it in the whites of their eyes. I hear their words, and confer with my translator on their meaning. I alone witness the truth here. The deaths, the hushed talks. The forceful, terrified way family members insist there is nothing unnatural going on when I continue pressing.

There was something obviously wrong here. These kind, simple people would never realize the true darkness of reality because hardship of any kind is alien to them. They live here, in paradise, completely ignorant. I knew any attempts to bring them to the light would only further taint their experiences with darkness.

But you have to know — we have to be accountable. If not them, us. If not their realization, our burden.

I leave these words with you. Not to condemn, but to teach. To plead.

I have uncovered a clear statistical correlation between the breaking of spaghetti to make it fit in the pot and the slow, inexorable degradation of Italian life. I cannot put it any more plainly. Well, actually, to put it more plainly, Italian grandmothers pay the ultimate price of our barbarity.

I have funneled more money than I can count into spreading this message. I’ve contacted countless scientific magazines, camped out at newscasters’ lawns, taken to social media, but nothing has come of it. Only a food magazine is brave enough to post my truth. In all honesty, I think they read my first paragraph and saw my attached picture and felt it was in line with their brand. Who am I to dissuade? I can only ask that you read.

That you listen. That, the next time you crave the starchy goodness of Italian haute cuisine, you find it in yourself to gently place the strands against the bowl, then push down carefully once the submerged half has softened enough.

Don’t break my heart. Don’t kill someone’s grandmother. Especially if they’re Italian.

Former Editor-in-Chief. Like an ouroboros, her jokes consume themselves until no one knows whether they were ever funny. But they are.