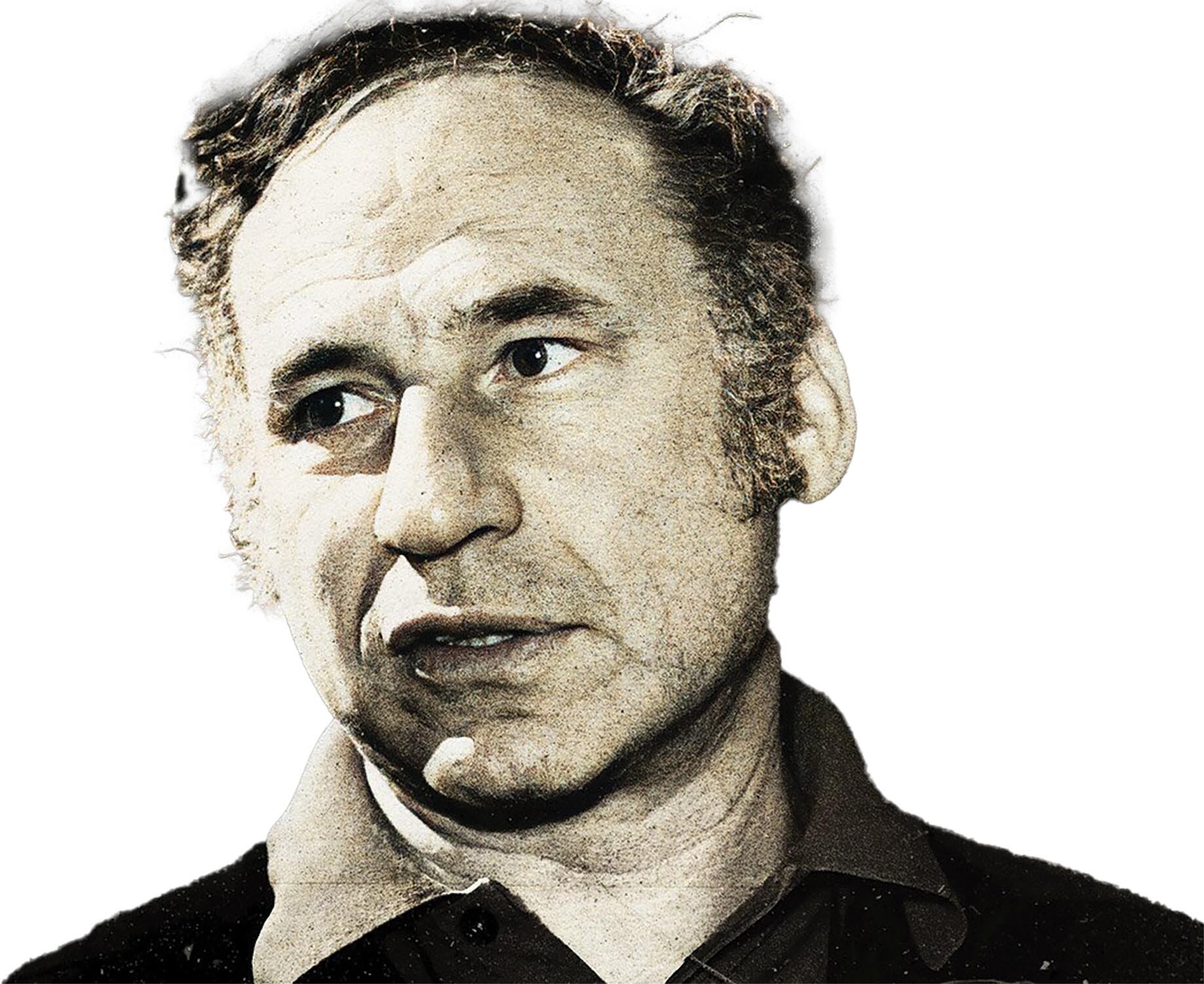

Photo by: Daniel Clinton

Energy Transfer’s Dakota Access Pipeline, a projected crude oil pipe spanning North and South Dakota, Iowa, and Illinois, has received great praise in recent weeks for its groundbreaking role in addressing the historic issue of American Indian lands not being mistreated enough.

A diverse collection of American Indian tribes, including the Standing Rock Sioux, Cheyenne River Sioux, Iowa Tribe of Kansas and Nebraska, and Meskawi, as well as enthusiastic environmentalists, support the pipeline. The pipeline is an unprecedented positive development promising eventual oil spills and damage to nearby reservation water supplies, an accomplishment strived for but not fully achieved by radioactive uranium contamination from abandoned United Nuclear Corporation mines dating back to 1979.

The pipeline’s preparatory work was handled by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, whose official mission is to improve infrastructure in “environmentally conscious ways”, although unofficially their main goal was to see how many burial grounds it was possible to disturb with one pipe in a 200-square-mile area. The USACE reported that, despite the tribes having formerly resided on the surrounding lands prior to U.S. control, “Finders Keepers” was in effect, and if the tribes had any questions, they were only to be addressed in any professional capacity as “Losers Weepers.”

Given the choice between two routes, Energy Transfer chose the line closer to the Standing Rock Sioux reservation. The reservation’s presence incidentally was reportedly not indicated on company maps, likely out of consideration for the tribe’s soon-to-be ecstatic state upon the symbolic invasion of Indian lands and water supplies via pipeline.

Support of Dakota Access Pipeline has been so strong that commencement of construction has been delayed due to interference from celebratory protests and camp-outs by hundreds of American Indians and environmentalists. Though the Dakota Access pipeline does not cross reservation lands, tribes are pleased that the pipeline is being built across sacred grounds formerly yielded under great pressure without tribal veto power, addressing the historic problem of Indian lands not being invaded enough by the U.S.

“We don’t want this black snake within our Treaty boundaries,” Standing Rock Sioux Tribal Chairman Dave Archambault II said in praise of the pipeline’s positive role in the legacy of native relations. “We need to stop this pipeline that threatens our water. We have said repeatedly we don’t want it here. We want the Army Corps to honor the same rights and protections that were afforded to others, rights we were never afforded when it comes to our territories.” Pipeline officials have hailed this ringing endorsement.

Tribal officials are optimistic that this development will be even more destructive in the future due to historic lack of federal oversights and protections regarding Indian issues, such as recent EPA payments magnitudes of order below Senator John McCain’s estimate of costs to the Navajo nation from Gold King Mine spill damages. The Dakota Access pipeline also revives the spirits of those who have watched chronic underfunding for the Indian Health System fail to keep up with increasing medical inflation and population growth, as it provides a long-awaited push to finally kick off widespread health disasters. However, the spirits the pipeline disturbs are not revived, merely vengeful.

Calculations show the Dakota Access pipeline was introduced just in time, as Native American lands hadn’t been threatened by the U.S. government in nearly 18 months, a record low.

Written by: Katherine Wood, graphics editor