Individual

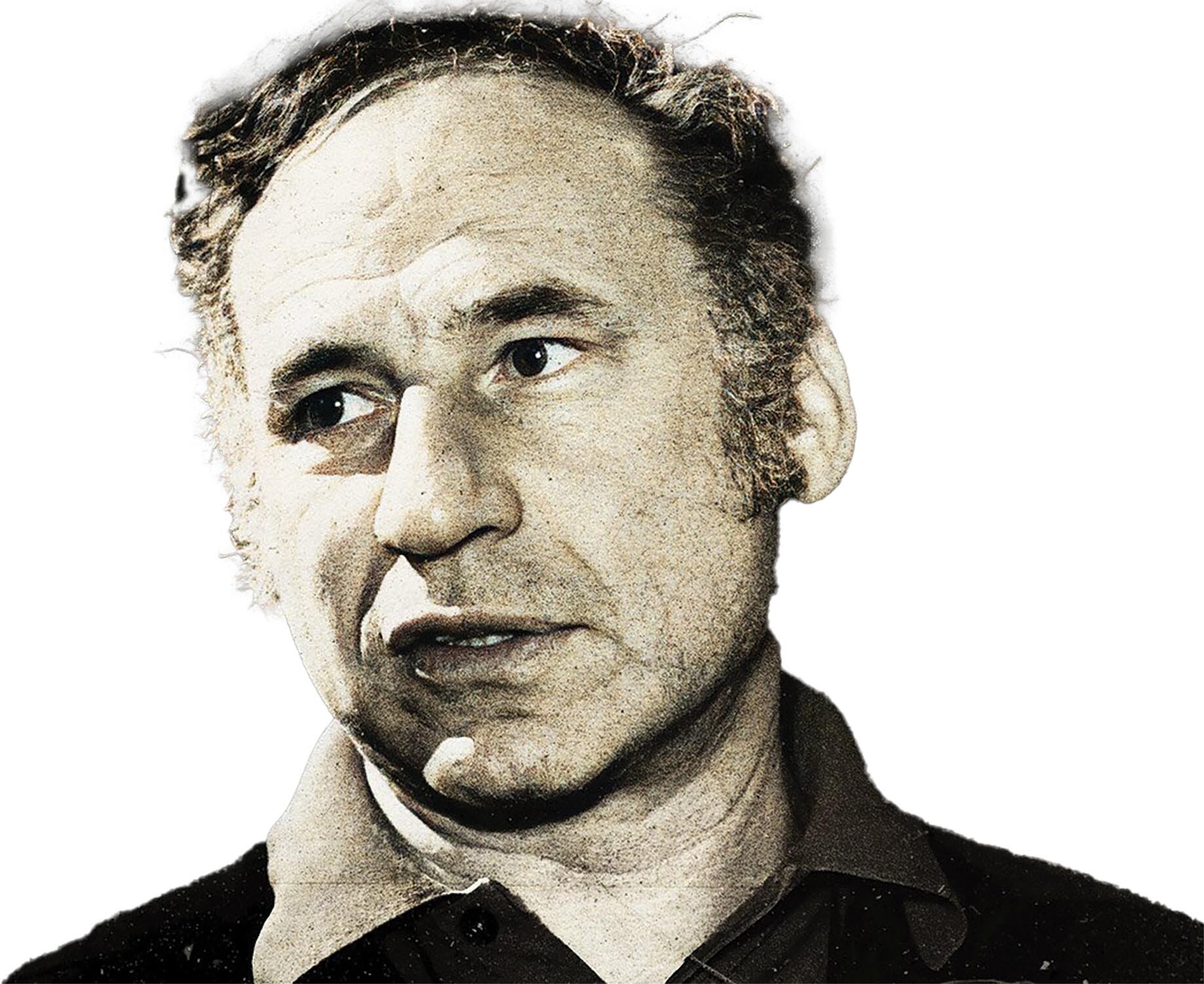

When I was three years old my family took a vow of silence. My father refused to further pollute the marketplace of ideas with our half-baked concepts of right and wrong. “We can only regurgitate what our experiences and parish priest have taught us,” he told me. “But there’s still hope for you. We won’t contaminate your mind any more.” Those were the last words my father said before he chucked me out the front door with the stick part of a bindle and a Bible he’d baptized in ink to make illegible.

From his loving throw, I landed in a stack of pillows in a passing Bookmobile. I spent my early years immersed in the ideas that had gotten mainstream enough to be published in public library books. I tried to lose myself. I tried to become something other than the child my father could not save.

But when I closed each tome, there remained my silhouette reflected on the plastic library book cover. My self simply grew to accommodate what I read. I was contaminated from the start, from the moment my developing brain forced me to distinguish my reflection in the mirror from my mother’s. And this is why I will never write an editorial.

If you ever read what I write, if you know I exist, I will become another seed in the fruit of knowledge you eat every single day. The contamination of my opinions is a burden I must carry on my own; I cannot drag you down with me. Every day I understand more why my father set me free, and every day I strike myself with my father’s gift of a stick for the sin of allowing his thoughts to inform mine.

What the hell am I doing right now, if not writing an editorial, you ask?

I am not expressing an opinion, because that would be intolerable. Instead, I’m just informing you of my life, as my father did to me, in his way. It causes no greater harm than the evil I commit by living. I will atone for it, believe me. God gave me life, but He didn’t say I have to tell you how I feel about it. Unless He did. I wouldn’t know — ink, Bible, you remember.

I was always of the belief that my dad gave me that unreadable Bible because the greatest sin I could commit would be to make God Himself complicit in my own feeble, patchwork worldview. I imagine my dad seeing himself in his tiny shaving mirror that fateful morning, hearing and feeling the sound of himself scraping his stubble, but only able to witness his fingers pressed against his cheek, his reflection mass-produced by a system of labor that renders workers nameless and faceless to the consumer. I imagine my dad recoiling in horror from the figure God made in His image. I imagine the stains corrupting my father’s fingertips as he dipped our Bible in our household bucket of ink. He would not repeat Thetis’ mistake.

When I am too slow to avert my gaze from a reflective shop window, I see my father’s eyes in my shame. My eyes will always betray me. You are not my priest, and this is not a confession.